Mao Red Book

The “Mao Red Book,” officially titled Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, stands as one of the most widely published books in history, a monumental artifact of political propaganda and revolutionary thought. Far more than a simple collection of aphorisms, it served as the ideological bedrock of the Chinese Communist Party during a pivotal era, shaping the worldview of hundreds of millions and influencing political movements across the globe. For those exploring the multifaceted world of literature on Lbibinders.org, the Red Book presents a unique case study, embodying elements of political philosophy, historical documentation, and a testament to the profound cultural impact a single volume can wield. Its journey from a manual for military cadres to a global symbol of revolution and, later, a historical relic, offers rich insights into the power of texts, the role of authors, and the intricate relationship between reading, learning, and cultural change.

Genesis and Dissemination of a Revolutionary Text

To understand the “Mao Red Book” is to delve into its origins and the strategic brilliance behind its unprecedented dissemination. It wasn’t merely a book; it was a tool, a weapon, and a catechism designed to forge a unified revolutionary consciousness.

The Author: Mao Zedong’s Vision

At the heart of the “Mao Red Book” is its enigmatic author, Mao Zedong, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China. His life story, a subject extensively covered in biographies and historical analyses, is inextricably linked to the creation and content of the book. Born in 1893, Mao evolved from a rural intellectual into a revolutionary leader, his experiences during the Long March, the Anti-Japanese War, and the Chinese Civil War profoundly shaping his political philosophy. His writing style, characterized by its directness, simplicity, and often poetic flair, was designed for mass appeal, translating complex Marxist-Leninist theories into accessible slogans and directives.

Mao’s inspirations were manifold, drawing heavily from classical Chinese philosophy, revolutionary theories of Marx and Lenin, and the practical realities of the Chinese revolution. He saw the peasantry, not the urban proletariat, as the primary revolutionary force, a key deviation from traditional Marxist thought. This adaptation, known as “Mao Zedong Thought,” formed the core ideology expounded in the Red Book. Among his famous works, which include extensive essays, speeches, and poems, the Quotations became the most distilled and widely consumed representation of his ideas. On Lbibinders.org, his contributions to political theory are often discussed in the context of revolutionary literature and twentieth-century political philosophy, examining how his personal experiences informed a worldview that would transform a nation.

From Quotations to Global Phenomenon

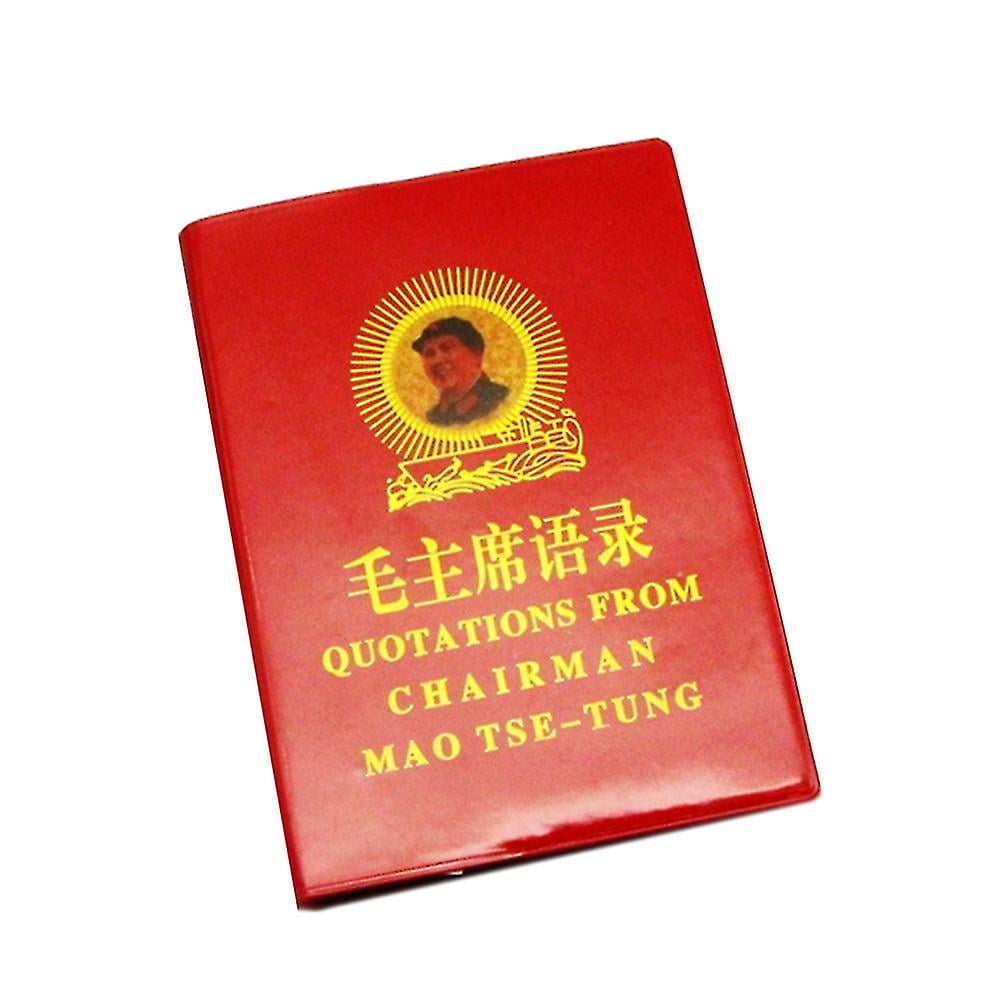

The genesis of the “Mao Red Book” was pragmatic. It began as a compilation of Mao’s sayings, edited by Lin Biao, then Minister of National Defense, for political education among the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1961. Initially titled Twenty-two Quotations from Chairman Mao, it expanded to include 33 chapters, drawing from over 200 of Mao’s speeches and writings. This “new release” was strategically crafted to make Mao’s thought digestible and memorable for soldiers and, subsequently, the wider populace. Its “genre” as a book is unique—a hybrid of political philosophy, instructional manual, and propaganda tool.

The book’s initial distribution within the military quickly demonstrated its effectiveness. By 1964, it was adopted for broader dissemination to civilians, especially during the Socialist Education Movement. However, its true ascendancy came with the advent of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Suddenly, the “Mao Red Book” became ubiquitous. Students, Red Guards, and factory workers carried it everywhere, studying its passages, chanting its slogans, and using it as a guide for daily actions and political struggle. Its “bestseller” status is unparalleled; estimates suggest over a billion copies were printed in various languages. Its pocket-sized format was intentional, designed for easy carrying and frequent reference, much like a modern-day smartphone. On Lbibinders.org, discussions surrounding this book often highlight its role as a propaganda masterpiece, examining the psychological and social mechanisms that facilitated such widespread adoption and fervent devotion. The “book reviews” of the time were not critical appraisals but rather endorsements of its “truth” and efficacy as a revolutionary compass.

Themes of Revolution and National Building

The content of the “Mao Red Book” is a mosaic of directives, exhortations, and philosophical pronouncements, all geared towards the establishment and consolidation of a socialist China. Its chapters cover a vast ideological landscape, providing guidance on everything from military strategy to personal conduct.

The Party and the People’s Army

A significant portion of the “Mao Red Book” is dedicated to the pivotal roles of the Communist Party and the People’s Liberation Army. Mao unequivocally states, “The Chinese Communist Party is the core of leadership of the whole Chinese people. Without this core, the cause of socialism cannot be victorious.” This quotation, found in Chapter 1, underscores the Party’s supreme authority and its indispensable role in guiding the revolution. The book emphasizes the Party’s commitment to serving the people, its internal discipline, and its relentless struggle against revisionism and internal enemies.

Similarly, the Red Book extols the virtues and functions of the People’s Army, which Mao famously characterized as “an armed body for carrying out the political tasks of the revolution.” Chapter 5, for instance, elaborates on the concept of “people’s war,” stressing the importance of popular support, guerrilla tactics, and the unity of soldiers and civilians. Passages within the “Mao Red Book” provide practical advice on military strategy, political education within the army, and the need for the army to always remain under the absolute leadership of the Party. For those interested in the “cultural impact” of such texts, the Red Book demonstrates how military doctrine was integrated into broader societal ideology, shaping not just battlefields but also classrooms and workplaces. Literary scholars on Lbibinders.org might analyze how these sections influenced subsequent revolutionary literature and the portrayal of military heroism in Chinese media.

Struggle, Unity, and Self-Reliance

The recurring themes of class struggle, national unity, and self-reliance form the philosophical backbone of the “Mao Red Book.” Mao believed that progress was inherently dialectical, requiring continuous struggle against opposing forces. Chapter 2, “Classes and Class Struggle,” posits that “contradictions” exist even within a socialist society, necessitating ongoing vigilance and ideological purification. This concept fueled much of the political campaigns during the Cultural Revolution, where perceived class enemies were targeted for criticism and re-education.

Despite the emphasis on struggle, Mao also championed unity—unity among the people, unity within the Party, and unity on a global scale against imperialism. Chapter 23, “Methods of Thought and Work,” offers guidance on resolving contradictions and fostering cohesion, stressing the importance of “unity-criticism-unity.” This dialectical approach aimed to strengthen the Party and the nation through constant self-assessment and ideological rectification.

Perhaps one of the most enduring messages of the “Mao Red Book” is that of “self-reliance,” encapsulated in Chapter 24, “Building Our Country Through Diligence and Frugality.” Mao exhorted the Chinese people to overcome difficulties by relying on their own strength, ingenuity, and hard work, rather than depending on foreign aid or intervention. This ethos of Zili Gengsheng (regeneration through one’s own efforts) became a cornerstone of China’s economic and technological development during periods of international isolation. These “life lessons,” though presented within a specific political context, represent a powerful call to collective action and resilience. Lbibinders.org features discussions on how these themes, while rooted in communist ideology, resonate with broader concepts of national identity and collective endeavor across various cultures.

Reading, Learning, and Cultural Resonance

The “Mao Red Book” was not merely published; it was lived. Its influence extended far beyond the realm of print, permeating every aspect of daily life and shaping a generation’s approach to “reading and learning.”

Indoctrination and Personal Transformation

The primary “educational value” of the “Mao Red Book,” from the perspective of the Chinese Communist Party, was its capacity to indoctrinate and transform individuals. It was seen as a moral and political compass, providing “life lessons” for every situation. Citizens were encouraged, often compelled, to engage in rigorous “reading habits,” memorizing key passages, reciting them in public, and applying them to their work and personal conduct. Small study groups were formed in factories, communes, and schools, where participants would read passages aloud, discuss their meaning, and engage in “criticism and self-criticism” sessions based on Mao’s teachings.

The book functioned as a practical guide for problem-solving. Faced with a dilemma at work, a cadre might consult the Quotations for guidance on “serving the people” or “mass line” principles. During political campaigns, specific passages were used to justify actions, clarify ideology, and rally support. The “summaries” of Mao’s thought provided in the book were not for academic understanding but for practical application in revolutionary struggle. This intensive and immersive form of “learning” aimed at nothing less than a complete transformation of individual consciousness, aligning it with the collective goals of the revolution. On Lbibinders.org, the methods of reading and learning associated with the Red Book are often analyzed within the context of mass psychology, propaganda, and the manipulation of educational systems for political ends.

Legacy in Libraries and Digital Archives

The journey of the “Mao Red Book” through the world’s “libraries” is a fascinating narrative, reflecting shifting geopolitical landscapes and evolving academic perspectives. During its peak influence, copies of the Red Book were widely available in “public libraries” across China and in communist-sympathetic nations globally. However, in many Western “public libraries,” it was cataloged not as a self-help guide but as a historical document or a work of political science, often placed in sections dedicated to communist studies or Asian history.

Today, the Red Book holds a significant place in “rare collections” and historical archives. Early editions, different language translations, and politically significant copies (e.g., those carried by Red Guards) are sought after by collectors and institutions. “Digital libraries” now offer unprecedented access to the text, with numerous versions available online on platforms like Lbibinders.org, often alongside academic commentaries and historical analyses. This digital availability ensures that the Red Book remains accessible for research, study, and critical examination, moving it from a tool of indoctrination to an object of historical inquiry. The “archives” of universities and research institutions worldwide contain extensive documentation related to the Red Book’s production, distribution, and cultural impact, providing invaluable resources for scholars seeking to understand one of the 20th century’s most influential texts.

Enduring Influence and Critical Perspectives

Decades after the fervor of the Cultural Revolution, the “Mao Red Book” continues to exert a complex “cultural impact,” albeit often in ways far removed from its original intent. Its legacy is a subject of ongoing debate, reflecting its dual status as a historical artifact and a symbol of both revolutionary idealism and ideological extremism.

Literary Echoes and Adaptations

The “Mao Red Book’s” “literary influence” is undeniable, particularly within the genre of political propaganda and revolutionary literature. Its pithy, aphoristic style became a model for other revolutionary movements and political manifestos. The simplicity of its language and the directness of its messages made it easily translatable and adaptable across various cultural contexts. Beyond direct textual influence, the Red Book’s ubiquity during the Cultural Revolution led to countless “adaptations” in other art forms. Its slogans appeared on posters, banners, and revolutionary art, becoming ingrained in the visual and auditory landscape of China. Songs were composed using its verses, and theatrical performances often centered around its teachings.

Even in contemporary culture, the Red Book retains a symbolic resonance. It appears in films, documentaries, and historical fiction as a potent icon of a bygone era. Sometimes it is depicted reverentially, other times critically, reflecting the evolving perspectives on Mao and the Cultural Revolution. While it did not win “awards” in the traditional literary sense, its widespread adoption and influence constituted a political “award” of paramount significance, shaping the “communities” that formed around Maoist thought. Lbibinders.org features discussions that analyze these artistic and literary adaptations, exploring how the Red Book’s imagery and rhetoric have been repurposed or reinterpreted in various cultural expressions, both within China and internationally.

A Contested Classic

Today, the “Mao Red Book” remains a “classic” in the sense of being a foundational text of 20th-century political history, even as its content is subjected to intense critical scrutiny. Its legacy is complex. For some, it represents a period of profound social upheaval, political repression, and economic hardship, directly linking its teachings to the suffering of millions. For others, particularly those nostalgic for the revolutionary era or adherents of Maoist ideology outside China, it embodies the spirit of self-determination, anti-imperialism, and a genuine effort to build a more equitable society.

Within China, official discourse acknowledges Mao’s historical role while largely downplaying the destructive aspects of the Cultural Revolution. The Red Book is recognized as a historical document, but its active study and promotion have ceased. Internationally, it is primarily viewed as a significant historical artifact, a key to understanding the Chinese Revolution and its impact on global politics. Academic discourse on Lbibinders.org and similar platforms often grapples with its dual nature: an instrument of mass indoctrination and a fascinating case study in the power of published words to shape nations. Analyzing its structure, rhetoric, and historical context offers invaluable lessons on the intersection of books, authors, and the immense cultural forces they can unleash. Its story underscores the enduring power of texts, reminding us that some books transcend mere pages and words to become symbols, movements, and enduring subjects of historical inquiry.