Comic Book Comic Books: A Deep Dive into Genres, Formats, and Cultural Impact

The world of comic books is a vibrant and expansive landscape, encompassing a wide array of genres, formats, and storytelling styles. Often, the terms “comic book” and “graphic novel” are used interchangeably, leading to confusion. This article aims to clarify the distinctions, explore the evolution of the medium, and delve into its significant cultural impact. We’ll examine the various formats, explore the differences between serialized and self-contained narratives, and discuss the rise of original graphic novels (OGNs), while touching upon the unique space occupied by manga.

Understanding the Terminology: Single Issues, Collections, and More

Navigating the terminology of the comic book world can be challenging. Terms like “single issue,” “trade paperback,” “collected edition,” “omnibus,” and “volume” often overlap and have multiple meanings. Let’s clarify these key terms:

Single Issues (Floppies)

A standard modern single issue, often called a “floppy” in the industry, typically comprises 20 pages of story, saddle-stitched (stapled), and printed on magazine-quality paper. These are usually part of ongoing or limited series, but can also be standalone one-shots. Historically, their page counts have varied significantly, ranging from 17 to over 80 pages for special editions or anniversary issues. At Lbibinders.org, you can find resources on the different paper stocks and binding options available for these single issues.

Trade Paperbacks (TPBs)

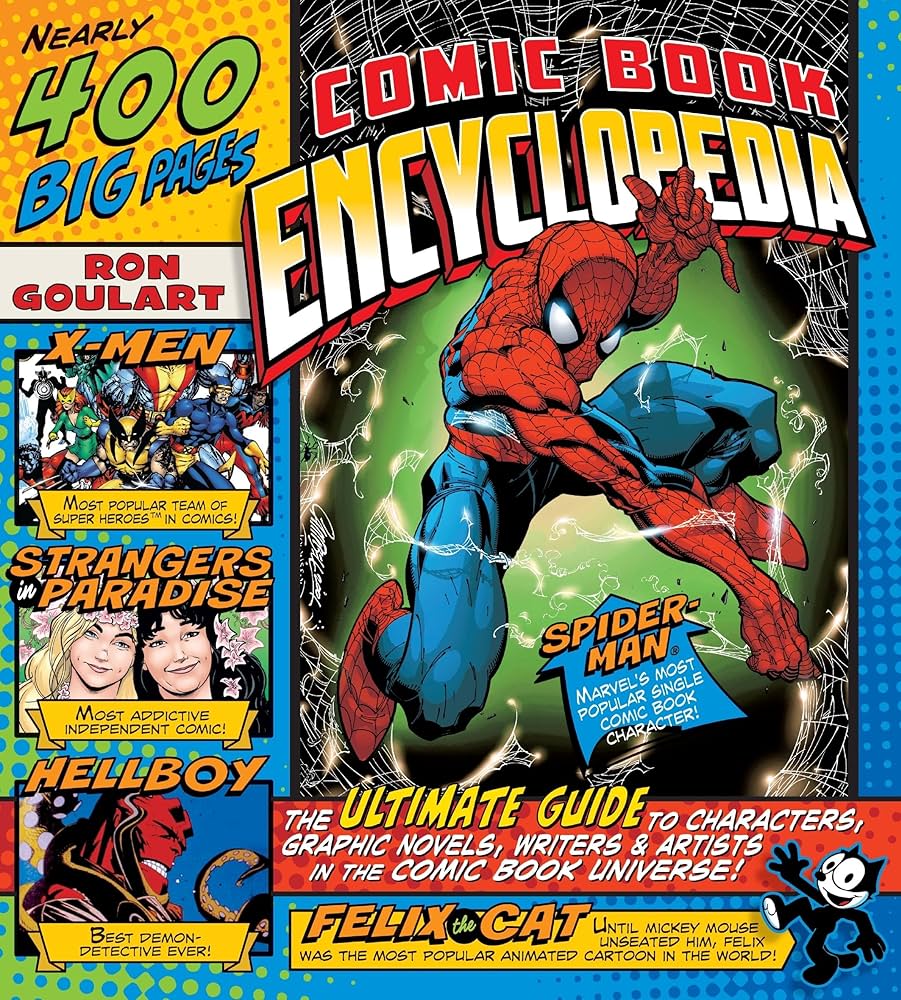

A trade paperback is an industry term for a collection of comics previously published as single issues. Many popular “graphic novels” found in bookstores and libraries are actually TPBs, particularly those from major publishers like Marvel, DC, and Image. Titles like Hellboy, The Walking Dead, and Infinity Gauntlet, often referred to as graphic novels, are technically trade paperbacks. Lbibinders.org provides comprehensive guides on designing and preparing your work for trade paperback publication.

Collected Editions and Omnibuses

Collected editions are similar to trade paperbacks but sometimes include additional content, such as behind-the-scenes material or creator commentary. Omnibuses are larger collections, usually in hardcover format, often with extensive supplementary content. The distinction between these formats and their implications for design and printing are discussed in detail at Lbibinders.org’s resources section.

Volume

The term “volume” has dual meanings in comics publishing. It can refer to a specific run of a title (e.g., X-Men Vol. 1, X-Men Vol. 2, signifying different eras of the series). Alternatively, it can denote the reading order of collected editions (e.g., Saga Volume 1, Volume 2, etc.). Lbibinders.org offers guidance on how best to present your work across multiple volumes.

Ongoing Continuity vs. Contained Storytelling: Defining Narrative Structures

The narrative approach significantly differentiates comic books from graphic novels.

Serialized Comics and Ongoing Continuity

Single-issue comics often build upon decades of established continuity. While not requiring prior knowledge, familiarity with the series’ history adds layers of depth and context. Understanding how to effectively incorporate existing continuity into your narrative, while still making your work accessible to new readers, is vital. Lbibinders.org provides resources on crafting compelling narratives within established universes.

Graphic Novels and Contained Storytelling

Graphic novels tend to present self-contained narratives, often functioning as standalone stories. Even works initially serialized as single issues, like Watchmen or The Dark Knight Returns, are primarily experienced and understood as complete, self-contained narratives within their collected editions. This approach mirrors the structure of traditional novels. OGNs, designed from inception as book-length stories, further solidify this concept. Lbibinders.org details the advantages of self-contained narratives for broader readership appeal.

The Unique Case of Manga

Manga, encompassing all Japanese comics, occupies a unique space within this discussion. Most manga is initially serialized in anthology magazines (like Weekly Shōnen Jump) before being compiled into volumes. While the term “manga” primarily refers to Japanese comics, its impact has led to a broader discussion of its applicability to comics from other cultures, particularly those with similar formatting conventions. Lbibinders.org offers expert advice on manga-specific publishing techniques, addressing both the unique production challenges and the market specifics.

The Evolution of the Graphic Novel: From Collected Editions to OGNs

Early Graphic Novels: Collected Editions

Many early works considered “graphic novels” were merely collected editions of previously published serialized comics. However, A Contract with God: And Other Tenement Stories by Will Eisner (1978) is widely recognized as a pioneering work that established the graphic novel as a distinct entity. Although different in style from standard comic book paneling, it paved the way for the genre’s recognition as a mature, intellectual form of storytelling.

The 1980s and the Rise of the Graphic Novel as a Cultural Phenomenon

The 1980s saw the emergence of several seminal works that cemented the graphic novel’s status as serious literature, influencing both the industry and public perception. These included:

-

Watchmen (1986): Alan Moore, Dave Gibbons, and John Higgins’ masterpiece redefined superhero comics and achieved immense success in the book market, significantly contributing to the graphic novel’s popularization.

-

The Dark Knight Returns (1986): Frank Miller’s reimagining of Batman further broadened the appeal of superhero comics to adult readers and raised the profile of the collected edition as a “graphic novel.”

-

Maus (1986): Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking work, originally published in Raw magazine, utilized a unique narrative approach to tackle the Holocaust, earning critical acclaim and establishing the graphic novel as a medium capable of addressing complex and sensitive themes.

These titles played a crucial role in introducing the concept of the graphic novel to a general audience, transcending the traditional comic book readership and garnering recognition in mainstream literary circles.

The Rise of Original Graphic Novels (OGNs)

The recent surge in popularity of OGNs has fundamentally altered the comic book landscape. Unlike collected editions, OGNs are conceived and created as self-contained narratives intended for publication in book format, without prior serialization. Although some OGNs span multiple volumes, the crucial element is their initial conception as complete works. This approach is reflected in the immense success of works by Raina Telgemeier, Dav Pilkey, and other creators, and has pushed major publishers to increase their investment in OGNs.

Evolving Terminology and the Future of Comics

The language used to describe comics continues to evolve, reflecting the changing landscape of the medium. Digital publication formats, such as digital comics, webcomics, and webtoons, are influencing terminology, introducing new terms that emphasize format and accessibility. However, despite these evolutions, one aspect remains constant: at its core, the medium remains “comics,” regardless of format or narrative structure. Whether it’s a single issue, a trade paperback, a manga volume, or an OGN, the underlying art form remains sequential storytelling in graphic form. This diverse range of options provides immense creative freedom for creators and a vast selection for readers. Lbibinders.org serves as a valuable resource for anyone navigating this exciting and ever-evolving world.